Levi White-An Oral History

Tramping routes and tracing roots with an inveterate woodsman.

Levi Louis White

Best to bring a map when you sit down at the kitchen

table with Levi Louis White. His stories make tracks. They'll tug you north

from Clintonville, White's home for thirty-four years, to the mines of

Lyon

Mountain, stray west to a dam he worked on in Malone; mosey south to

a fishing hole in Lake Placid; then over to a power-line job in Tahawus;

and up to Peru, where he was born and firmly intends someday to be buried

alongside his wife and a tribe of Whites three generations deep and maybe

more if you count their ranks before the name change,when they were LeBlancs

drifting off the tired fields of Quebec. By the time he's hauled you over

to Clintonville, ten miles by the back road from his birthplace in Laphams

Mills, the northern Adirondack map may be as crisscrossed as a Christmas

ham, a clove for every town, and for every town a tale.

New Russia? Underneath a bridge is a bank

he and his dad heaped up with riprap. Rand Hill? Where bootleggers tried

to get the old man to smuggle booze by horse-drawn sled across the border.

"He could've drawn an awful load of it, lot more than in the cars, but

he wouldn't. Afraid he'd get caught and it would cost him more than it

was worth." Lewis? Met a girl when he was working on a woods job. Liked

her. Married her. Glad he did. Willsboro? Irvin Calkins's mill. Skidded

wood there. Kept him busy all winter long.

Not much glamour in these gigs; White, a spry

man of eighty-three, was no Great Camp caretaker, hermit, guideboat builder

or legendary guide. The Yankee notables whose biographies plump the pages

of county histories-homesteader turned mining magnate, legislatot, judge-this

is not his story. White's legacy is easier to miss. Among French-Canadians

and their Franco-American descendants, the emphasis was less on the acquisition

of land (and the assumption of political power that accrues to a propertied

elite) than on a relationship with the land that stressed know-how and

experience. The land was yours through working it. White's people, he says,

"didn't own. They were sharecroppers. They rented. All small, ten-or twelve-cow

farms. I lived on eight or ten farms before we moved for a year to Massachusetts."

If you take home to mean more than a titled

plot and read it as a region, a known, loved terrain, then surely Levi

Louis Whit~who rarely says the word, "Adirondacks," and not once in conversation

invoked the name of the Adirondack Park-is as much the classic Adirondacker

as any icon in the canon. The kind of flexibility and mobility he brought

to his employment, for example, may look like the expression of a restless

soul, but think about it. To make a living in the Adirondac~to live a life

that lets you stay her~you have to be versatile enough to take the

place on its own terms, do a little mining, logging, road work. You let

the seasons parcel out the opportunities, and as seasons change so do the

jobs, and as jobs change, so will your address. What doesn't change is

the landscape. Titles come and go but the land stays put.

The enterprising White left no line of North

Country work unsampled. Farmed with his father, helped his grandfather

with his traplines. Beat the dew off golf links in Lake Placid with a bamboo

pole. No construction job was beyond his reach; logging was a constant.

As one industry thrived, then foundered and was replaced by another, White

kept pace. When vacationers sluiced into the back roads of the region,

he met a need there too, renting out roadside cottages. The trajectory

of his career mirrors the course of the Adirondack century. As for tracking

it, take a cue from an old memory:

"I was ten when I started rabbit hunting with

my uncle. Oka~ he'd say, you find a fresh rabbit track and you stay on

that track and I'll stay tight here. I'd say, I'll get lost! You won't

get lost, he'd snap. You lose the track, you're gonna get lost. You don't

lose it, you'll end up right here. See, a rabbit always makes a circle

and he ends up back where he comes from. Most animals do in the woods.

I was following that rabbit, thought I was about nine miles from my uncle

when~boom.? I was back where I started. My uncle took the end of that rabbit's

nose off. Didn't want to spoil the meat."

The story's good, and not just because it's

funny. It's about the way White tells a story, the way he's lived his life.

You may feel like he's leading you to hell and gone, but like that rabbit,

he will not get you lost. Sooner or later you're going to wind up where

you started, which in White's case tums out to be rural Clinton County.

"I'm named after both my grandfathers, Levi

Doner and Levi Louis. My father's name was Louis White and he was born

in 1894. There are three Louis Whites in the Peru cemetery, and I'm Levi

Louis or I'd've been the fourth. My grandfather was living with us until

he died. His father, Louis White II, was in the Civil War, fifth cavalry

from Peru. Had a lot of horses shot out from under him but he never got

a scratch. It must've been the one before him changed the name from LeBlanc

to White. He's the only one I never met.

"My grandfather on my mother's side ran a

trapline on the Peasleeville River. Fur peddlers came around with a horse

and buggy. They'd haggle back and forth like horse jockeys, finally arrive

at a price. They could have gone a lot farther but they wanted to pick

up all the furs they could. My grandfather bought an Empire State stove

from one of them. You couldn't break

it with a sledgehammer. Wouldn't surprise me if that old stove was

still up there too.

"All our old folks, my father and mother,

would talk French. But when they'd talk to us, they'd talk English. It

should've been the other way around. We would've had to learn English anyway.

I learned French tunes from my father and mother. They used to harmonize

together when we were going along the road in a car. Oh, it

was beautiful."

White also evidently soaked up the French-Canadian

affinity for tall tales. One he tells concerns the old Haff farm

in Peru. In Clinton County histories, settler

John Haff is cited

for his pioneering zeal, his building skills and his wizardry with pancakes-but

the supematural qualities of Haff's hardware escapes mention. When White

was three, his father leased the place.

"John Haff was a Dutchman, one of

the first settlers of Peru village. In one of those old farms was an old-fashioned

latch on the door to the cellar and at night you'd hear that latch go clickety-click.

Well, my father got sick of that. He bent some nails over it. Still clicked.

You could sit right there and look at that damn thing, I did it myself,

it wouldn't move but it'd still click. You

got to where you could live with it."

White, warming up now, leans over lunch, Twinkies

and a cup of cold coffee. "Here's another one. Used to be a little village

up there at Franklin Falls. Nothing now hardly. Anyway this guy from Franklin

Falls had a pair of black horses hooked to a market wagon with a seat in

the front and the back like a pickup. He came down to Au Sable Forks to

get groceries and stacked them all along the back, and he started back

to Franklin Falls, and all at once he noticed this big black cloud. Put

the

whip to them little black horses, and the storm kept getting closer

and closer-that's a long ways up and down some real steep hill~and that

storm come up to the tailgate and almost up to his groceries. But not quite.

Now, if you want to believe that one...

White holds my gaze with a stern look and works on his Twinkie.

"This one here's about a fellow at Franklin

Falls, came along with a rifle, saw a buck on the other side of the river,

so he shot him. Bullet went through the buck and hit a partridge sitting

in a limb. Well, the river wasn't froze and he had knee-high boots on,

so he picked up the partridge and the buck and dragged them across the

river. By the time he got to the other side his boots were frill of water

so he dumped them out. He had twenty-five trout in his boots. All that

in one shot.

"Take it or leave it. I left it."

In 1923 White's father got a job heading a

crew of road builders around Mirror Lake. By then, said White, "all our

relatives had got Out of farming and were working for the Lake Placid Club.

Women were chambermaids, the men were [working] on the golf course." At

nine years old, White too was working, hawking Cloverine salve and balsam

pillows to his neighbors. "Kind of skis I had, they were made of pine or

maple, cheap, you know. I used my skis for snowshoes and went all over

the

swamp looking for balsam for my great-aunt. She made the pillows which

I peddled door to door."

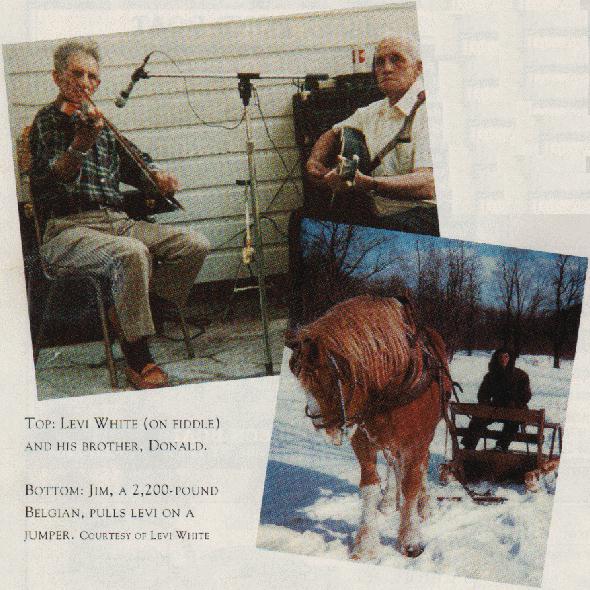

Round about this time White picked up the

violin, thanks to the free gift of a fiddle from Cloverine. "I had leamed

from the music teacher in school to read enough music so I could sing a

song. Kept the scales right tucked in the fingerboard and I played the

notes over until I got to where I could put my finger on any note I wanted

without looking. Then I began trying to sing what I could play and trying

to make the same noise with my fiddle as my voice, and all at once it started.

It broke loose and away I went.

"I got four fiddles now. One of them my father

bought for me, the first good fiddle I ever had. I was probably thirteen,

fourteen. He paid thirty-five dollars for it. I don't know how he did it

working for five dollars a day but he said if you're gonna play fiddle,

you gotta have a good fiddle. It was in Curly LeRoux's barbershop. Somebody

left it in there for a haircut. A guy tried to teach me how to play but

you don't make a right-handed player out of a left-handed one. So I changed

the strings over and taught myself. Willis Wells, the town supervisor of

North Elba, offered to send me to music school, buy my clothes, pay my

board and pay for the cost of teaching me violin. He said think it over

and I did. Probably by this time I would've been a concert violinist instead

of a lumberjack or a miner or whatever. But I wanted to stay with my family.

I never regretted that."

One of White's more influential mentors, Hiram

Henry Hanmer, also had a violin. "He claimed it was a Stradivarius, and

boy I never heard a violin sound so nice. He taught me and so did his sister,

Orsie. Fussy about the music, just like him. She played the mandolin. Hanmer,

he used to come to Peasleeville, play at some of these square dances at

my grandfather's. They called them kitchen hops, played right into daylight.

Cider, pies, roast beef, homebaked bread, rolls. They would play until

morning, people would go home, sleep all day, come back and play again

the next night, and that'd go on three or four nights. Then they'd roll

on to somebody else's house. Mostly dancing and just fiddle music.

In White's fifteenth summer, Hanmer, who rented

guideboats on Paradox Bay took on White as an assistant. "A Scotchman:

he saved everything. I used to catch frogs and minnows for him and put

them in a big box with a screen on it and keep it in the lake, sell 'em

to the fishermen. He taught me to put a worm on a hook. You start with

the worm's head and slide it right on

like this, leave that much sticking out so the tail'd wiggle, see,

and the bass'd hit it like bang, bang, bang. He could catch fish where

there wasn't any.

"One day two old guys came along with their

fishing tackle, people with money. Hanmer couldn't go but Levi'll take

you out, he said, Levi knows where the fish are. Well, I had no idea where

the fish were, but I knew there was a tree that had fallen into the water,

uprooted somehow, leaves still on it, so I suspected it was attracting

fish. Cast over there, I said, and see what happens. Boom! They pulled

bass after bass out of there, one right after the other. After we got back

they said, you're right, that guy knows, all right.

"And I had no more idea'n the man in the moon."

"I couldn't swim and I'll tell you another

little secret. Most of those old guides couldn't either. But I liked being

in a boat. Hanmer had two guideboats he claimed he made himself, such a

hard finish they looked like glass. He was scared somebody'd put a scratch

on them so they just stayed up on the rack. Every last nail, no matter

what size, he saved. When I saw driftwood or a board floating, I had to

pick it up and saw it to the right length for firewood. Hanmer showed me

how even a junk pile could look neat."

A better mentor even than Hanmer was White's

own father; sooner or later, White's memories meander back to him. "My

father could take a horse that I couldn't make do anything work right along

with him. He had a knack. Just before he died he took a horse, looked like

a Belgian but wasn't. I couldn't get that horse to draw. My father couldn't

walk very fast and couldn't breathe good but he said let me give her a

try. He got her to draw. He outdrew us all.

"I worked under him at the Malone municipal

airport. On the Schroon Lake Road, up through St. Huberts. He went to Wanakena

and we built a dam. He would take sixty men into a construction job in

the woods, three or four loaders, couple of shovels, ten trucks, and he

would never mark down any time on any of them until he got home at night

and then he got it all perfect. Kept a time book in his pocket and he never

wrote a note."

White Sr. could take credit too for introducing

Levi to the love of his long life. "It was her mother's house we were staying

in. There were eight of us on a woods job, my father paying dollar and

a half a day for room and board. They were glad to have us because they

were hard up for money. Most of us were hunters so we supplemented the

pork and beans with venison. Madeline Mabel Daniels was her name. I was

twenty-three, she was seventeen. Her mother's name was Wells. They were

all French, had the build of these Canadian trappers, all short and squatty.

"She helped me in the woods. Drove a skidding horse

while I cut wood. She'd take a block of maple this big around and pick

it right up and slam it up there on the back of the truck. Never used a

wood hook, she did it by hand. Strong! That's what they found out at the

beer joint here when she was tending bar. Old Jim Smith was beating hell

out of a little guy in the corner, she came out from behind the bar, grabbed

him by the collar, gave him a yank and said, now Jim, you get back up on

that stool and you stay there. Alright, Madeline, he says. Alright."

The young couple tried their hand at tenant

farming for a while, working for a Clintonville man who, remembers White,

"was giving me something like thirty dollars a month and my house rent,

firewood, eggs and milk. The firewood you cut yourself. Never got any money

until the end of the month and by that time he had it all charged up to

the store for groceries so we ended up with three or four dollars. Well,

that lasted three or four months. Then I got out of there. I could make

more money in the woods."

Then came a stint in the mines. In 1940 the

twenty-five-year-old White rented a small camp in Chateaugay, five miles

from the iron mine at Lyon Mountain. "All kinds of foreigners in the mines:

Polish, French, Irish and Italians. The Poles, they made a career of that

mining. They were right at home in the mines. One Italian worked with us,

Angelo his name was. If you want to hear about one of them close calls!

Angelo and I and my brother-in-law Gordon were mucking up the ore off the

rail track. Three of us would muck up about seven cars a day. That's seven

tons apiece or forty-nine in eight hours. All at once Gordon says hold

it. You know an old miner's reflexes is quicker'n greased lightning. We

heard a little click. I made a dive but I wasn't fast enough. Old Angelo

reached out with his hand and grabbed me by the belt and away we went,

both of us. And here come a cartwheel down the middle of that tunnel about

this high and this thick. What probably happened was some blasting on another

level shook something loose.

"My brother-in-law and I used to stand on

that last car and bum a ride up so we wouldn't have to walk the mile to

the chute puller, and that tail-end car would whip back and forth. Your

lamp Only shines so far, you're peering out over the edge, and all at once

here comes a low spot. Down you go. One of them come out with no head.

He didn't duck. And he was supposed to get married the next day.

"I came off work one day and found the timekeeper.

Said, I want my slip. I can make more money in the woods."

White got Out of mines a lot more easily than

the mines got out of him. "Iron was the catalyst for all the other industries

around here," he reminds me. "They had to have mules and oxen to haul the

iron from here to Port Douglas, and they had to have hay to feed the mules,

and farmers to grow the hay. Everything depended on everything else." This

by way of defending his recent vocation: clambering around the bat-ridden

bowels of the winter ore bed of a long-defunct mine a mile from his house

and piecing together an ancient waterpowered turbine.

"We found a hundred feet of railway shaft,

a vertical three-inch drive shaft, a set of bevel gears and a bunch of

blasted-down iron ore they never took out.," The treasure of the Sierra

Madre it's not, but the project's got White flying higher than the time

he was drilling bedrock for the power line at Tahawus; his drill kicked

up, "and booted me so high I could see over the trees to where them guys

was up at the top of the hill digging. Broke my arm. Drove myself to the

hospital. I had to wait nine weeks before it healed. So it was back in

the woods again. Wherever I was, I always ended up back in the woods."

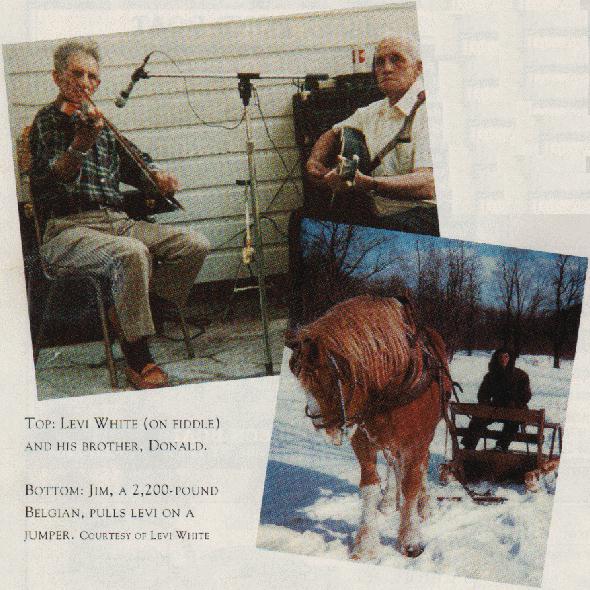

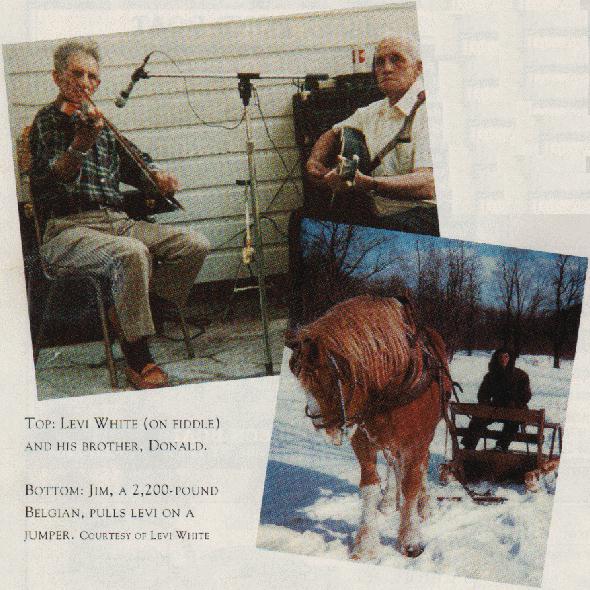

It's been a while since White has skidded

with a horse. But if you think he doesn't miss it, try sorting his box

of photographs: uncles, daughters, horses, parents, horses, army buddies,

sons and grandson, horses and more horses back of those. Four grown children

live near to him and more grandchildren than he cares to count, and clearly

he is glad for their company. But it's the horse pictures that bring the

stories.

"I've always had a horse. And I'm not unhorsed

yet. My little buckskin out the window there, that's Betsy. Now, this horse

Sandy, he would do anything you told him. Tum left, right, back up, all

on command. And there's a picture of Old Bill. Homeliest horse in the world.

You didn't have to put a bridle on that horse. He'd do it all himself.

If you had some logs on top of the mountain and you wanted to bring them

down, you'd hook them onto Old Bill. That horse would go out of sight of

you, come to a stump, stop. Pull one way, that didn't work. Go the other

way, pull it just a little, just like that, and he'd get it by the stump.

They've tried to make remote control things to match a horse. They can't

do it."

All this horse talk leads me back like that

rabbit and I have to ask the obvious. He echoes my query: "What do I like

best about the woods?" It's a question I expect he'll need to think about,

but his answer is confident and swift. "The quiet. I learned this trick

from a guy whose mother was a full-blooded squaw. You make yourself like

a stump. You just sit there quiet, don't turn your head, turn your eyes

instead, pretty soon you'll see two or three little birds, maybe a chipmunk,

some squirrels. And they get used to that stump sitting there, you see.

You won't sit too much alone."

By Amy Godine

Adirondack Life November/December 1997

Rod Bigelow (Roger Jon12 BIGELOW)

P.O. Box 13 Chazy Lake

Dannemora, NY 12929

rodbigelow@netzero.net

rodbigelow@netzero.net

BACK TO THE HISTORY

PAGE

BACK TO BIGELOW

HOME PAGE